In this captivating southern state, seven distinct regions form a living museum where indigenous traditions, revolutionary cuisine, and artistic innovation create Mexico’s most compelling cultural tapestry

[display-map id=’2892′]

In Oaxaca, mornings aren’t something you wake up to — they gather around you. The cool air carries traces of wood smoke and wildflowers. A vendor’s call rises from a side street. Church bells mark time in a city where it often feels irrelevant. The markets stir, the mountains watch, and the day begins in no particular hurry.

Oaxaca has become something of a pilgrimage site for travelers seeking authentic Mexican experiences. Yet despite growing international attention, the state remains gloriously itself—neither calcified in tradition nor surrendering to the homogenizing forces of modernity. Instead, Oaxaca demonstrates how cultural preservation and evolution can coexist, creating spaces where indigenous knowledge systems and contemporary creativity engage in constant, dynamic dialogue.

How to Pronounce Oaxaca: A Quick Guide for Travelers

One of the most common questions I hear from fellow travelers planning a trip to this incredible region is, “How do you even say Oaxaca?” It’s a valid question, as the spelling can be a bit tricky for English speakers! But mastering the pronunciation is a small step that makes a big difference in connecting with locals and showing respect for the rich culture and its indigenous heritage.

So, let’s clear up the mystery:

Oaxaca is pronounced wah-HAH-kah.

Let’s break it down syllable by syllable:

- wah: This sounds like the beginning of the word “water” or “wander.”

- HAH: This is the key syllable. The ‘x’ in Oaxaca is pronounced like a strong, guttural ‘h’ sound, similar to the ‘j’ in Spanish words like ‘jalapeño’ or ‘hola.’ Think of it like a soft, aspirated “hah” sound, as if you’re gently clearing your throat.

- kah: This sounds like the “ca” in “car”.

Putting it all together, you get wah-HAH-kah.

Many people initially try to pronounce the ‘x’ like the ‘x’ in English words like “xylophone” or “extra,” or they might ignore the ‘h’ sound altogether. But once you get the hang of that distinct ‘HAH’ sound, you’ll be saying “Oaxaca” like a local in no time!

Taking the time to learn the correct Oaxaca pronunciation not only helps you navigate the region with more confidence but also opens doors to warmer interactions. Locals truly appreciate the effort, and it’s a wonderful way to show your engagement with the place and its people. So go ahead, practice saying “wah-HAH-kah” a few times – you’re one step closer to immersing yourself in the soul of Oaxaca, Mexico!

A Territory of Magnificent Diversity

Understanding Oaxaca begins with recognizing its stunning geographical diversity. The state encompasses soaring mountains, arid valleys, cloud forests, and tropical coastline—all within an area roughly the size of Indiana. This varied landscape has historically limited travel between regions, allowing distinct cultures to develop in relative isolation.

The result is a cultural mosaic unparalleled in Mexico: 16 officially recognized indigenous groups, each with their own language, culinary traditions, textile arts, and spiritual practices. While Spanish serves as the lingua franca in urban centers, venture into the highlands or remote valleys and you’ll discover communities where Zapotec, Mixtec, or Mixe remain the primary languages.

This diversity presents itself most vividly when exploring Oaxaca’s seven regions—each offering distinct experiences for travelers willing to venture beyond the capital city.

Oaxaca City: Colonial Elegance and Creative Energy

The historic center of Oaxaca City unfolds around its zócalo (main square) in a dignified grid of pedestrian-friendly streets lined with exquisitely preserved colonial architecture. Behind colorful facades in varying states of perfectly imperfect preservation, internal courtyards create tranquil retreats from the city’s energy.

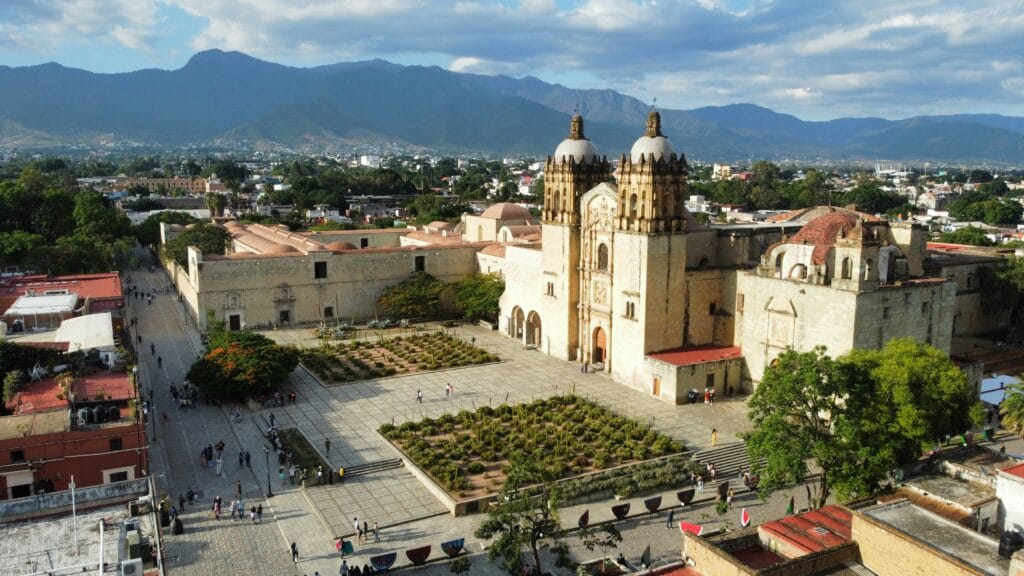

Early mornings offer a magical quality as golden light plays across the green cantera stone of the Santo Domingo church, widely considered among Mexico’s most beautiful religious structures. Inside, the Temple of Santo Domingo dazzles with its gilded Baroque ornamentation so elaborate it nearly overwhelms the senses—a physical manifestation of Spanish Catholicism’s determination to awe indigenous populations into conversion.

The attached former monastery now houses the excellent Museum of Oaxacan Cultures, where the treasures of Tomb 7 from nearby Monte Albán demonstrate the technical sophistication and artistic sensibility of pre-Hispanic civilizations. The museum’s thoughtful curation creates context for the cultural experiences awaiting throughout the state.

Beyond monumental attractions, Oaxaca City rewards wandering. The pedestrianized Macedonio Alcalá teems with galleries, boutiques, and cafés. Particularly noteworthy is the stretch between the zócalo and Santo Domingo, where artists have established studios showcasing contemporary interpretations of traditional arts. Standouts include the Taller-Galería Shinzaburo Takeda, where the Japanese-born master printmaker has trained generations of Oaxacan artists, and Archivo Magon, displaying politically charged graphic arts that continue Oaxaca’s tradition of social consciousness.

The Central Valleys: Ancient Civilizations and Living Villages

Radiating from the capital in three directions, Oaxaca’s Central Valleys contain archaeological wonders and vibrant indigenous communities often separated by just a few miles—creating a landscape where past and present exist in visible layers.

The Zapotec ceremonial center of Monte Albán commands a flattened mountaintop with 360-degree views of the valleys it once dominated. Established around 500 BCE and abandoned around 750 CE, the site’s main plaza creates a powerful sense of ceremonial space with its precisely aligned buildings and massive scale. Arrive early to experience the complex in relative solitude, when morning mist sometimes shrouds the valleys below, creating the sensation of floating above the clouds.

Less visited but equally compelling, Mitla showcases exceptional geometric stonework unlike anything else in Mesoamerica. Its intricate mosaic façades feature over 14 different design patterns that scholars believe may represent a form of iconographic writing. The nearby Tlacolula Sunday market offers a glimpse of the regional economy that has connected indigenous villages for centuries.

Throughout the valleys, dozens of communities specialize in particular crafts, often with techniques pre-dating Spanish arrival. In Teotitlán del Valle, weaving cooperatives produce textiles using natural dyes derived from indigo, cochineal insects, and local plants—continuing practices established over two millennia ago. The village’s community museum, Balaa Xtee Guech Gulal, provides cultural context through exhibits curated by community members rather than outside academics.

In San Bartolo Coyotepec, the López Núñez family has pioneered innovative techniques with the region’s distinctive black clay pottery while maintaining traditional firing methods. Their workshop offers demonstrations where visitors can appreciate the physical skill and generational knowledge required to transform humble clay into objects of remarkable refinement.

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec: Matriarchal Power and Cultural Pride

The eastern region where Oaxaca narrows between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean has developed a culture famous for the economic and social power of its women. In cities like Juchitán and Tehuantepec, Zapotec women known as “las tehuana” have historically controlled the regional economy through market trading, creating societies with distinctly matriarchal characteristics celebrated in the paintings of Frida Kahlo.

The region’s most spectacular cultural display occurs during the Vela festivals, particularly the Vela Sandunga in Tehuantepec each May. These celebrations feature women wearing elaborate traditional garments including the distinctive huipil grande—heavily embroidered blouses that can require months to complete and represent significant financial investments. The full costume includes a resplandor, a starched lace headdress that frames the face like a Renaissance portrait.

The isthmus also nurtures Mexico’s most visible muxe community—individuals who constitute what anthropologists describe as a third gender within Zapotec culture. Neither precisely equivalent to Western transgender identity nor to the Two-Spirit traditions of North American indigenous groups, the muxe tradition demonstrates how indigenous cultures often maintained more fluid concepts of gender before European contact.

The Sierra Norte: Cloud Forests and Community Ecotourism

North of Oaxaca City, mountains rise dramatically into misty highlands where pine-oak forests transition to cloud forests draped with epiphytes and moss. This biodiverse region hosts remarkable community-based ecotourism initiatives collectively known as the Pueblos Mancomunados—eight Zapotec villages that have united to protect their communal forest lands while creating sustainable economic opportunities.

The villages have constructed modest eco-lodges, trained local guides, and established well-marked hiking routes connecting communities through spectacular natural settings. Trails wind through landscapes where orchids bloom beside mountain streams and waterfalls cascade down moss-covered cliffs. Rare species like the resplendent quetzal and margay can occasionally be spotted by quiet, observant hikers.

What distinguishes the Pueblos Mancomunados model is its authentic community control—unlike many ecotourism projects managed by outside interests, these initiatives direct benefits to community members while operating according to traditional governance systems. Visitors participate in genuine cultural exchange rather than staged demonstrations, staying in accommodations constructed from local materials using sustainable techniques.

The village of Benito Juárez offers particularly accessible facilities for first-time visitors, with well-appointed cabins and guides conversant in basic English. More adventurous travelers might explore Latuvi or Amatlán, where deeper immersion rewards with experiences like joining community tequio (collective work projects) or participating in temascal (traditional sweat lodge) ceremonies guided by local curanderos (healers).

The Mixteca: Textile Treasures and Dominican Masterpieces

The northwestern region of Oaxaca rises into dramatic mountains where Mixtec communities have maintained distinctive cultural traditions despite centuries of economic challenges. This area contains remarkable colonial-era Dominican churches that blend European architectural forms with indigenous artistic sensibilities.

In Yanhuitlán, Coixtlahuaca, and Teposcolula, 16th-century Dominican complexes feature massive stone construction with elaborately carved façades incorporating both Christian iconography and subtle elements from pre-Hispanic symbolism. These buildings functioned as more than religious spaces—they were comprehensive cultural centers housing schools, hospitals, and workshops where indigenous artisans developed the hybrid artistic styles that characterize Mexican sacred art.

The Mixteca region maintains Mexico’s oldest continuous traditions of backstrap loom weaving, particularly in villages like Santa María Zacatepec, where cotton textiles feature complex brocade designs passed through generations of women. Unlike the better-known textiles of the central valleys, Mixtec weaving often incorporates abstract representations of natural elements and cosmological concepts dating to pre-Hispanic codices.

The Coast: Afro-Mexican Heritage and Marine Sanctuaries

Oaxaca’s Pacific coastline stretches 370 miles across bays, coves, and beaches ranging from developed resort zones to pristine wilderness. Beyond the tourist centers of Huatulco and Puerto Escondido, coastal communities maintain distinctive cultural traditions blending indigenous, Spanish, and African influences.

The Costa Chica region acknowledges its Afro-Mexican heritage through distinctive music, dance, and culinary traditions born from historical communities established by escaped and freed enslaved people. In villages like Collantes and Corralero, cultural expressions like the chilena dance and percussion-driven regional music demonstrate cultural connections to both African origins and local indigenous communities.

For nature enthusiasts, the Laguna de Manialtepec offers bioluminescent nighttime boat excursions, while Mazunte hosts the Mexican National Turtle Center protecting endangered marine species. Between December and March, boat tours from Puerto Ángel provide opportunities to observe humpback whales during their annual migration.

Mezcal Country: Beyond the Trend to Tradition

While mezcal has become an international spirits trend, understanding this complex distillate requires experiencing it in its cultural context. The Central Valleys and southern Ejutla region contain hundreds of small-scale producers (palenqueros) creating mezcal using methods that have evolved little over centuries.

Unlike industrialized spirits, traditional mezcal production follows agricultural rhythms and cultural practices that enhance its status as Mexico’s most terroir-expressive distilled beverage. The variety of agave species used, regional production methods, and even the waters used for distillation create distinct expressions that reflect Oaxaca’s biodiversity.

Visiting family palenques offers insight impossible to gain from commercial tastings. In Santiago Matatlán, multi-generational producers welcome visitors to witness their process—from the jimador harvesting pencas with their sharp coa tools, to the earthen pit roasting that imparts mezcal’s characteristic smokiness, to the horse-drawn tahona stone that crushes the fibers, and finally the copper or clay pot distillation.

The Real Minero palenque in Santa Catarina Minas maintains especially traditional methods, including clay pot distillation and cultivation of rare agave varieties. Their approach emphasizes sustainability through rigorous replanting programs and biodiversity conservation—important considerations as commercial pressure increases on wild agave populations.

Understanding mezcal culture means recognizing its ceremonial significance. Throughout Oaxaca, mezcal features prominently in rituals marking births, marriages, and deaths. The sharing of mezcal creates bonds between families and communities, with specific varieties reserved for particular celebrations.

Oaxaca Food: A Gastronomic Treasure

Food in Oaxaca stands as Mexico’s most diverse and technically complex regional tradition, built upon indigenous ingredients and techniques that have incorporated colonial influences without being dominated by them.

The state claims seven distinct mole varieties, complex sauces requiring dozens of ingredients and multiple preparation techniques. Beyond the internationally known mole negro with its chocolate undertones, explore lesser-known variations like manchamanteles (“tablecloth stainer”) combining fruits with chiles, or chichilo incorporating rare chilhuacle chiles and charred tortillas.

More than specific dishes, understanding the food in Oaxaca means appreciating fundamental techniques: the nixtamalization process that transforms corn into nutritionally complete masa; the distinctive smoking of chilies to create layers of flavor; the use of clay vessels that impart mineral qualities to dishes.

For culinary travelers, the Central de Abastos market in Oaxaca City offers comprehensive exploration of regional ingredients. Beyond tourist-oriented sections, the sprawling market contains specialized areas for herbs, chiles, and unique ingredients like chilacayote squash and huitlacoche (corn fungus considered a delicacy).

Regional markets provide even more authentic experiences. The Sunday market at Tlacolula brings together vendors from throughout the eastern valley, creating a sensory immersion as Zapotec grandmothers in traditional dress haggle over prices and specialized vendors prepare market foods found nowhere else—like crisp memelas topped with asiento (pork fat paste) and quesillo (Oaxacan string cheese).

For deeper understanding, cooking schools like the Seasons of My Heart, established by culinary historian Susana Trilling, offer classes connecting food preparation to cultural context. Students learn traditional techniques while engaging with the stories and cultural significance behind Oaxaca’s distinctive dishes.

Festivals and Spiritual Life: Where Ancient and Catholic Merge

Oaxaca’s ceremonial calendar layers Catholic observances onto indigenous traditions, creating syncretic expressions where pre-Hispanic spirituality remains visible beneath Christian structures.

The most renowned celebration, Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), transforms Oaxaca during late October and early November. While commercialization has affected some aspects, in communities like Xoxocotlán and Etla, the observances retain profound spiritual significance. Families construct elaborate ofrendas (altars) featuring photographs of departed loved ones surrounded by marigolds, copal incense, and favorite foods to guide souls back for annual reunions. Cemetery vigils blend solemn remembrance with celebration of life’s continuity—candles illuminate grave sites while bands play the favorite music of the deceased.

Less internationally known but equally significant, the Guelaguetza festival in July showcases distinctive traditions from each of Oaxaca’s regions. The name derives from the Zapotec concept of reciprocal exchange and mutual support—communities present their unique dances, music, and costumes in a celebration that simultaneously honors indigenous heritage while demonstrating Oaxaca’s collective cultural wealth.

In villages throughout the state, patron saint festivals blend Catholic and indigenous elements in ways that reveal the incomplete nature of colonial conversion. In communities like San Bartolomé Quialana, processions featuring Catholic imagery incorporate pre-Hispanic elements like ritual cleansings and offerings to earth deities, demonstrating how indigenous cosmologies have maintained continuity beneath Catholic structures.

Practical Considerations

Getting There: Oaxaca’s international airport connects to major Mexican hubs and select U.S. cities. Alternatively, first-class buses from Mexico City offer comfortable overnight service through spectacular mountain scenery.

Getting Around: Within Oaxaca City, walking is ideal for central areas. For regional exploration, rental cars provide flexibility for central valleys and coastal regions, while community-operated shuttles serve Sierra Norte villages. Private guides with vehicles offer efficiency for multistop regional exploration.

When to Visit: October through April offers consistent dry weather. The shoulder months of May and September provide good conditions with fewer visitors. July features the Guelaguetza festival but also peak rainy season afternoon showers.

Where to Stay:

- In Oaxaca City, Hotel Casa Oaxaca offers refined accommodations in a restored colonial mansion with an exceptional restaurant.

- For Sierra Norte exploration, the community eco-lodges of Pueblos Mancomunados provide authentic immersion.

- On the coast, Hotel Escondido near Puerto Escondido offers sophisticated design in a tranquil setting away from party scenes.

Language: While tourist areas have English speakers, venturing into indigenous communities may require basic Spanish. Learning a few phrases in Zapotec or Mixtec shows respect when visiting traditional villages.

A Suggested 10-Day Itinerary

Days 1-3: Oaxaca City Explore the historic center, Santo Domingo cultural complex, and key museums. Take a cooking class focusing on traditional techniques. Visit the Saturday Etla market for artisanal foods and crafts.

Days 4-5: Central Valleys Archaeological Sites Visit Monte Albán early morning, followed by artisan villages including Teotitlán del Valle (textiles), San Bartolo Coyotepec (black pottery), and San Martín Tilcajete (alebrijes—fantastical carved wooden figures).

Days 6-7: Sierra Norte Experience the cloud forests and indigenous communities of Pueblos Mancomunados, staying in community eco-lodges and hiking between villages.

Days 8-10: Pacific Coast Explore the coastal region around Puerto Escondido or Mazunte, visiting turtle sanctuaries, bioluminescent lagoons, and beaches. Optional detour to the coffee-growing communities in the southern Sierra Madre.

Oaxaca rewards travelers who approach with openness and respect for its cultural depth. Beyond collecting experiences or photographs, visitors who engage thoughtfully find themselves transformed by encounters with traditions maintaining unbroken connections to ancient knowledge systems. In a world of increasing homogenization, Oaxaca demonstrates how cultural continuity and innovation can coexist, creating communities where identity remains strong while engaging creatively with modernity’s challenges.

Author’s Note: When visiting indigenous communities, remember to ask permission before taking photographs, especially of religious ceremonies or individuals. Direct purchases from artisans and community-run enterprises ensure tourism benefits reach local people authentically preserving Oaxacan cultural traditions.