Where ancient Maya wisdom and colonial grandeur blend with natural wonders far from the resort crowds

The first light of dawn breaks over the stone temples of Ek Balam, casting long shadows across grounds still untouched by the day’s visitors. In the distance, roosters announce morning’s arrival from a nearby Maya village, where hands pat out fresh corn tortillas just as they have for millennia. This is the Yucatán Peninsula that exists parallel to—yet worlds away from—the all-inclusive resorts and nightclubs of Cancún and Playa del Carmen.

Travel through the peninsula reveals a profound truth: when travelers venture beyond the hotel zone, they discover a Yucatán that transforms them. The peninsula doesn’t simply hold the remnants of Maya civilization—it cradles a living culture that continues to evolve while maintaining deep connections to its ancient past.

[display-map id=”2890″]

The Maya Heartland: Past and Present

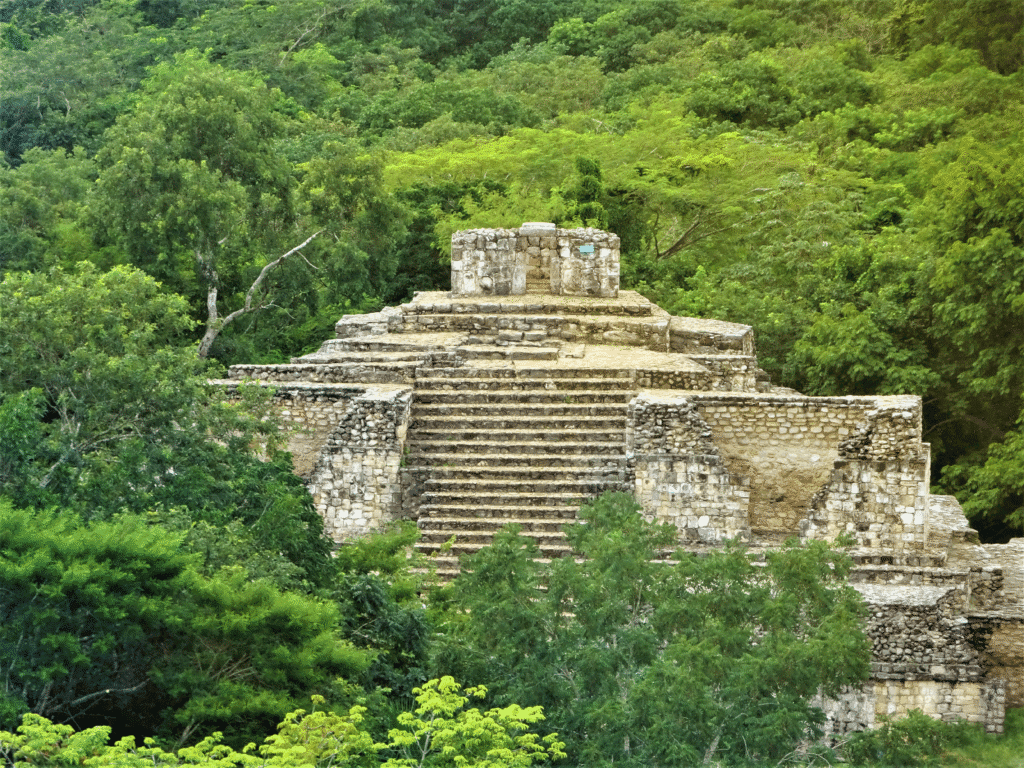

The Yucatán Peninsula comprises three distinct Mexican states—Yucatán, Quintana Roo, and Campeche—each with its own character yet bound by deep Maya roots. While Chichén Itzá draws crowds with its iconic pyramids (and rightfully so), the peninsula harbors dozens of archaeological sites where visitors can almost feel the presence of the spirits in relative solitude.

At Ek Balam, 105 miles west of Cancún, the recently restored Acropolis features some of the best-preserved stucco reliefs in the Maya world. Arrive at opening time (8 a.m.), and you might share the site with nothing but tropical birds and wandering iguanas. Unlike at many sites, climbing is still permitted on most structures, offering sweeping views of the jungle canopy from the 100-foot central pyramid.

Further inland, Coba remains delightfully wild, with structures emerging from tangles of vines and roots. Its network of ancient white stone roads (sacbeob) connects architectural complexes spread across miles of jungle. Look into the surrounding jungle and you can see mounds of stones that are yet to be excavated. If you’re lucky you might get to watch spider monkeys swing between ceiba trees that the Maya consider sacred connections between worlds.

For a truly off-the-grid experience, the remote site of Uxmal rewards the journey with its distinctive Puuc-style architecture featuring intricate geometric mosaics and imposing rounded pyramids. The site receives a fraction of Chichén Itzá’s visitors, creating an atmosphere where the imagination can more easily transport you back a thousand years.

Villages of Living Tradition

Throughout the Yucatán Peninsula, small communities maintain traditions that aren’t performances for tourists but simply the rhythm of daily life. Many villages welcome respectful visitors seeking authentic experiences beyond the tourist corridors.

In Tixkokob, families have been weaving hammocks—the traditional Yucatecan bed—for generations. The town is known for producing some of the finest hand-woven hammocks in Mexico, many featuring intricate macramé edges that can take months to complete. Several family workshops welcome visitors, and purchasing directly from artisans supports the continuation of these traditional crafts.

The village of Maní holds both spiritual and culinary significance. Here, Spanish friars infamously burned irreplaceable Maya codices in 1562, yet today the community is known for perfecting poc-chuc, thin slices of citrus-marinated pork cooked over open flames. The town’s restaurants serve this regional specialty according to recipes passed down through generations.

For a deeper connection, consider a community-based tourism experience in Yaxunah, where a local cooperative offers simple accommodations in traditional oval Maya houses with thatched roofs. Visitors can participate in milpa agriculture, traditional beekeeping, and cooking classes where you’ll learn to prepare cochinita pibil in an underground pit oven.

Sacred Waters: Cenotes in Central Yucatán

The Yucatán Peninsula’s limestone foundation is pierced by thousands of cenotes—natural sinkholes filled with crystalline groundwater that served as both water sources and sacred sites for the ancient Maya. While tour buses crowd certain cenotes near the Riviera Maya, countless others remain peaceful sanctuaries.

The Homun region contains over 300 cenotes within a small area, many operated by local cooperatives. At Cenote Kankirixche, descend a wooden ladder into a cathedral-like cavern where stalactites catch the light from a single opening in the ceiling. The families who steward these sites maintain simple facilities and appreciate visitors who show respect for the water’s sacred nature.

For adventurous travelers, the remote Ring of Cenotes near Chichén Itzá marks the impact zone of the asteroid that likely ended the dinosaur era. These perfectly circular water holes, visible from satellite imagery, offer unparalleled swimming experiences and connections to cosmic history.

In Maya tradition, cenotes are considered portals between worlds. Some communities still practice offering ceremonies before entering these sacred waters—a reminder that what tourists see as natural swimming pools hold profound spiritual significance for the local culture.

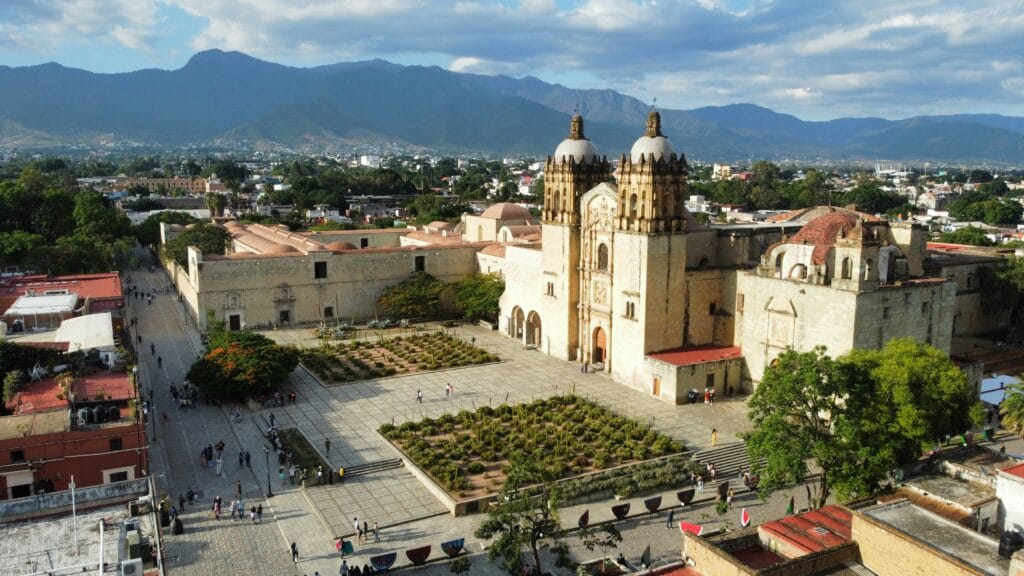

Colonial Jewels: Where Worlds Blend

The peninsula’s colonial history adds another layer of cultural complexity. In Valladolid, 100 miles west of Cancún, Spanish colonial architecture radiates from a central plaza where Maya families gather in the evening coolness. The city exemplifies the blending of cultures that defines the region.

Wander down calles lined with buildings painted in saturated yellows, blues, and terracottas to reach Casa de los Venados, a private home housing one of Mexico’s most significant collections of folk art. The owners offer morning tours with all donations benefiting local charities.

In the “Yellow City” of Izamal, every building in the historic center wears the same golden hue, creating an otherworldly atmosphere as sunrise light plays across the facades. The massive Franciscan monastery of San Antonio de Padua sits atop a destroyed Maya pyramid, a physical manifestation of cultural layering that defines the region.

For a truly unique experience, time your visit to coincide with the town’s festival honoring the Virgin of Izamal (December 8), when pilgrims arrive from across the peninsula for processions blending Catholic devotion with Maya spirituality.

The Yucatán Regional Cuisine: A Gastronomic Universe

Yucatecan cuisine stands distinct from other Mexican regional traditions, influenced by Maya ingredients, European techniques, and Caribbean spices. The region’s culinary heritage tells the story of its complex history—the sour orange from Spain, the habanero chile from the Caribbean, and the achiote seed paste from the ancient Maya all come together on the Yucatecan plate.

The iconic dish cochinita pibil—slow-roasted pork marinated in sour orange and achiote—exemplifies this fusion. For an authentic version, visit the Sunday market in the town of Tixcocob, where families have specialized in the dish for generations.

At the colorful market in Oxkutzcab, sample tropical fruits unknown outside the region—mamey sapote with its sweet pumpkin-chocolate flavor, black sapote reminiscent of chocolate pudding, and the custard-like cherimoya that Mark Twain called “the most delicious fruit known to man.”

For a comprehensive taste experience, the legendary Mercado Lucas de Gálvez in Mérida offers everything from fresh papadzules (egg-stuffed tortillas with pumpkin seed sauce) to tender relleno negro (turkey in charred chile sauce). The stalls with the longest lines of locals typically offer the most authentic flavors, particularly those serving chaya agua fresca, a refreshing drink made from a spinach-like plant revered for its medicinal properties.

Practical Considerations for Yucatán Peninsula

Getting There: Major airlines serve Cancún International Airport, but consider flying into Mérida’s international airport for easier access to the western section of the peninsula.

Getting Around: Rent a car for maximum flexibility, as public transportation between smaller towns can be limited. Roads are generally well-maintained, and rental agencies can be found in both Cancún and Mérida.

When to Go: November through March offers pleasant temperatures and lower humidity. September brings brief afternoon showers but fewer visitors and lush landscapes.

Where to Stay:

- In Valladolid, the lovingly restored Hotel Posada San Juan offers colonial charm with modern comforts.

- Near Uxmal, the Lodge at Uxmal allows for early morning site access before the day-trippers arrive.

- In Mérida, Rosas & Xocolate combines a historic mansion with contemporary design and a renowned chocolate spa.

Language: While tourism professionals often speak English, learning basic Spanish phrases shows respect. In smaller communities, some elders speak Maya as their first language, and learning a few words—”ma’alob k’iin” (good day) or “jach dyos bo’otik” (thank you very much)—will earn warm smiles.

A Suggested One-Week Itinerary

Days 1-2: Valladolid and Surroundings Begin in this colonial city, using it as a base to explore Ek Balam and nearby cenotes like Suytun and Xkeken. Dine at El Atrio del Mayab for traditional Yucatecan flavors.

Days 3-4: Izamal and Mérida Journey to the Yellow City, then continue to Mérida, the peninsula’s cultural capital. Explore the Paseo de Montejo, the city’s European-inspired boulevard, and time your visit to catch Sunday celebrations in Plaza Grande.

Days 5-7: The Puuc Route Drive the Puuc Route, stopping at Uxmal and lesser-known sites like Kabah and Labná. Stay near Uxmal to experience the evening light and sound show, then explore the nearby Loltún caves, where evidence of human habitation dates back 10,000 years.

Best Overall Time: December to April (Dry Season)

- Why go then: Pleasant, warm temperatures (mid-70s to mid-80s °F / 24–29°C), low humidity, little rain.

- Good for: Beaches, cenote swimming, Mayan ruins (like Chichén Itzá and Uxmal), and exploring colonial cities.

- Downside: Peak tourist season, especially December–January and during Easter/Spring Break, so higher prices and crowds.

Shoulder Season: May to June

- Why go then: Fewer tourists, lower hotel rates.

- Weather: Hotter (up to mid-90s °F / 35°C) and more humid, with occasional rain.

- Perk: It’s before hurricane season really ramps up, and the region’s lush jungles are vibrant.

Rainy / Low Season: July to October

- Why go then: Cheapest rates, quietest beaches, and authentic local vibe.

- Weather: Hot, humid, frequent afternoon storms, and it’s hurricane season (highest risk August–October).

- Good for: Travelers willing to gamble with weather to avoid crowds and save money. Still plenty of nice mornings before rain tends to roll in later.

Special Highlights

- Equinox at Chichén Itzá (March 20/21 & September 22/23): See the famous “serpent of light” on El Castillo.

- Day of the Dead (Oct 31–Nov 2): Beautiful traditions in towns like Mérida and Valladolid.

- Whale Shark Season (June–September): Snorkeling with these gentle giants off Isla Holbox and Isla Mujeres.

The Yucatán Peninsula rewards those who venture beyond the beach resorts with a multilayered experience where ancient wisdom, colonial heritage, and natural wonder intertwine. Traveling slowly, with open eyes and an open heart, reveals secrets that remain hidden to those in a hurry—a leisurely pace allows the peninsula’s magic to unfold naturally.

Author’s Note: When visiting Maya communities, remember that you’re entering living cultural spaces, not tourist attractions. Photography should always be preceded by permission, and contributions to community initiatives rather than individual handouts make the most positive impact.